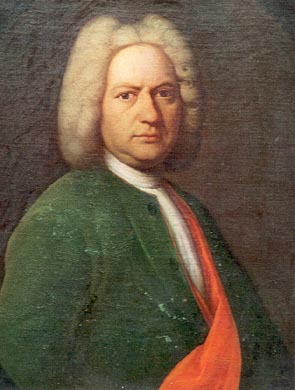

J.S. Bach

J.S. Bach

(excerpts from the book,

Bach, Beethoven and the Boys by David Barber)

Just about everybody in the Bach family was a good musician, but nobody was better than Johann Sebastian. If you wanted to you could trace the Bach family back through five generations. But you still wouldn't find anybody to bear J.S. Various members of the Bach clan were organists, town pipers and instrumentalists in Thuringia, a small state in the eastern part of what is now Germany. As far as being musicians, the Bachs had Thuringia pretty much sewn up.

Johann Sebastian's great-great-grandfather, old Veit Bach, was a miller. He liked to play his lute while the millstones ground flour in the background. J.S. later said it probably helped him to keep time. Johann Sebastian's father, Johann Ambrosius, married Elizabeth Lammerhirt, whose family were prosperous furriers and part-time mystics.

Johann Ambrosius had a twin brother named Johann Christopher. They looked so much alike that not even their wives could tell them apart. Johann Ambrosius and Elizabeth had three sons: Johann Christoph, Johann Jakob, and Johann Sebastian.

Johann Sebastian was born on March 21, 1685 and baptized two days later at the little church of St. George in Eisenach. At last report, the church still stands, and the present pastor still refers to that historic event whenever he baptizes a new little baby in the same font. Maybe he figures it will give them something to work towards.

At age eight, little Sebastian was sent of to school, where he did considerably better than his brother Johann Jakob. He was a good singer and was one of those pupils who always knows the answers to everything.

His mother died when he was nine and his father a year later, so Sebastian was shipped off to the little town of Ohrdruf to live with his brother Johann Christoph, who was an organist and a pupil of Johann Pachelbel -- the one who wrote the famous Canon. Since money was scarce it was soon decided to send little Sebastian to the choir school of St. Michael in Luneberg. The rules stated that the singers had to be the "offspring of poor people, with nothing to live on, but possessing good voices." He seemed to qualify on all counts, so off he went.

The school paid for his tuition, room and board, and gave him candles and firewood. When his voice broke, we are told, Sebastian sang and spoke in octaves for a week. It must have been an interesting effect, but it didn't last. Anyway, Sebastian was kept busy after that playing violin, viola, and organ.

One of the ways Bach learned about music was to copy the compositions of his predecessors. He did a lot of this while at school. Historian Cecil Gray says: "He absorbed all styles, instead of being absorbed by them." Karl Geiringer says something similar: "Young Sebastian absorbed all instruction as readily as a sponge does water."

For a while, Bach studied organ in Luneburg with Georg Bohm, who had been a pupil of a man named J.A. Reinken. Bach walked 30 miles to Hamburg to hear Reinken play. After arriving in Hamburg, Bach was hungry and tired from his long walk, but had no money for a meal. As he tells the story, he was just sitting outside an inn minding his own business, thinking about food and rubbing his tired feet, when out from an open window were tossed two herring heads. And as if that weren't enough, each fish head contained a Danish ducat.

(to be continued)

I will be taking an indefinite break from writing, resuming at some point in the future. I want to thank all of my readers and commen-tators for their loyalty. It has been a grand experience and I wish you all God's blessings, peace and happiness.

I will be taking an indefinite break from writing, resuming at some point in the future. I want to thank all of my readers and commen-tators for their loyalty. It has been a grand experience and I wish you all God's blessings, peace and happiness.